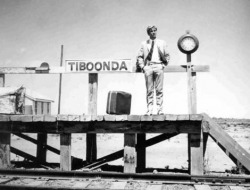

Wake In Fright (1971) – Ted Kotcheff

“The images of a nation, as it manufactures for itself and presents them to the world, will inevitably make themselves felt to a greater or lesser degree, overtly or covertly, in all its cultural artifacts. The most potent of such images through recurrence will gradually accrete the resonance and achieve the quintessence of myth, until eventually the line between myth and reality will be blurred in the national consciousness” (McFarlane). This notion as introduced by McFarlane is an interesting point, particularly when looking at the representation of the bush legend and the manifestation of masculinity in Australian cinema and television. Other concerns that he brings up in discussion are also relevant for this topic: the concept of ‘a man’s country’, mateship, anti-authoritarianism, Australia’s wide, open land, and lastly, competitive instinct. All these concepts are clearly evident in Ted Kotcheff’s Wake In Fright.

A Man’s Country: the main images ever portrayed about Australia are of males, and white males in particular, which has also been argued as a tool of oppression upon both indigenous groups and females. This is quite apparent in Wake In Fright particularly because the only women represented in the film are Jeanette (who is overtly promiscuous, she does not fit into the typical female stereotypes within Australian cinema) and John’s girlfriend in Sydney (who we only ever see in photos and his fantasies).

Mateship: “The sentimental idea of mateship might well be Australia’s chief contribution to the history of human relationship. Like most images which together constitute a national identity, the image of men as mates derives from that blurred territory between myth and reality” (McFarlane). This is a very interesting quote from McFarlane, insinuating that mateship as concept is significantly Australian, and in Wake In Fright clearly portrays this, in a somewhat perverted and intense way, and that it does not always have to be represented in a sentimental framework.

“No One Tells Us What To Do”: anti-authoritarianism has always been a distinctively Australian characteristic, and is clearly portrayed in most all aspects of Australian film and television, again in Wake In Fright. This concept stems from traditional ideals of being anti-British, anti-European, anti-laws, anti-boss, and anti-rules. McFarlane also provides an interestingly two-folded ideal to this concept as well, which is worth further discussion: “’No one tells us what to do’ can signify admirable resistance to outworn authority structures; it can also signify a mind closed to otherness”.

A Wide, Brown Land: in the representation of the bush in Wake In Fright, we see the landscape take on a terrifying emptiness within the rural town, but also within the characters themselves, who are just living day to day, with no real purpose or substance. Also here I would like to just quote a statement from McFarlane, which I find very intriguing, even though it is based upon the work of Peter Weir: “Weir is interested in the possible horror behind the verandas; for him, the mulberry faces are only pretending to sleep, and the dogs are more likely to be licking up blood”. I feel this can also be somewhat applied to Wake In Fright, most prominently in the tone within the film and the atmosphere it creates.

Competitiveness: there are numerous aspects to Wake In Fright that intensify this notion of competitiveness, most prominently within Australian males, specifically the way John’s life is unravelled from an illegal game of two-up (which the police do not stop), and also through the way the band of men challenge one another in the experience of kangaroo hunting and their drunken escapades following. This is intense viewing, particularly because it becomes a grotesque relationship between the men, where they bait one another, even in their drunken state, to the point of almost bashing each other to death, but all is good the next day, mateship still intact.

A Man’s Country: the main images ever portrayed about Australia are of males, and white males in particular, which has also been argued as a tool of oppression upon both indigenous groups and females. This is quite apparent in Wake In Fright particularly because the only women represented in the film are Jeanette (who is overtly promiscuous, she does not fit into the typical female stereotypes within Australian cinema) and John’s girlfriend in Sydney (who we only ever see in photos and his fantasies).

Mateship: “The sentimental idea of mateship might well be Australia’s chief contribution to the history of human relationship. Like most images which together constitute a national identity, the image of men as mates derives from that blurred territory between myth and reality” (McFarlane). This is a very interesting quote from McFarlane, insinuating that mateship as concept is significantly Australian, and in Wake In Fright clearly portrays this, in a somewhat perverted and intense way, and that it does not always have to be represented in a sentimental framework.

“No One Tells Us What To Do”: anti-authoritarianism has always been a distinctively Australian characteristic, and is clearly portrayed in most all aspects of Australian film and television, again in Wake In Fright. This concept stems from traditional ideals of being anti-British, anti-European, anti-laws, anti-boss, and anti-rules. McFarlane also provides an interestingly two-folded ideal to this concept as well, which is worth further discussion: “’No one tells us what to do’ can signify admirable resistance to outworn authority structures; it can also signify a mind closed to otherness”.

A Wide, Brown Land: in the representation of the bush in Wake In Fright, we see the landscape take on a terrifying emptiness within the rural town, but also within the characters themselves, who are just living day to day, with no real purpose or substance. Also here I would like to just quote a statement from McFarlane, which I find very intriguing, even though it is based upon the work of Peter Weir: “Weir is interested in the possible horror behind the verandas; for him, the mulberry faces are only pretending to sleep, and the dogs are more likely to be licking up blood”. I feel this can also be somewhat applied to Wake In Fright, most prominently in the tone within the film and the atmosphere it creates.

Competitiveness: there are numerous aspects to Wake In Fright that intensify this notion of competitiveness, most prominently within Australian males, specifically the way John’s life is unravelled from an illegal game of two-up (which the police do not stop), and also through the way the band of men challenge one another in the experience of kangaroo hunting and their drunken escapades following. This is intense viewing, particularly because it becomes a grotesque relationship between the men, where they bait one another, even in their drunken state, to the point of almost bashing each other to death, but all is good the next day, mateship still intact.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed